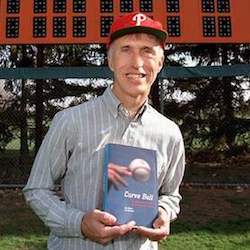

Jim Albert, co-author of Curveball: Baseball, Statistics and the Role of Chance in the Game , editor of the Journal of Quantitative Analysis and Sports , and professor of statistics at Bowling Green State University will join the Stats and Stories regulars to discuss why statistics and baseball have been linked for decades and how this connection has strengthened with the growing presence of sabermetrics in player and team management.

+ Full Transcript

Bob Long: If you've ever listened to major league baseball, you probably know play-by-play announcers love to just pepper you with lots of statistics. It used to be you'd only hear about things like batting averages, homers, pitcher's earned run averages, but today the stats have become much more sophisticated, like how often does the batter get a hit when the bases are loaded? I'm Bob Long, welcome to Stats and Stories; it's a program where we discuss the statistics behind the stories, and the stories behind the statistics. Our focus this time is on America's favorite pastime, baseball. But before we talk to our special guest for today, we wanted to find out about baseball stats more, and how they've changed so dramatically in recent years. So reporter JM Rieger gives us a few examples.

JM Rieger: In baseball, traditional statistical measures of a player's ability have always been the norm, but Miami University Statistics Professor Doug Noe says statistical models have changed not only how fans watch the game, but also how teams manage it.

Doug Noe: The role of statistics started off as being a very, very descriptive role, and over time it's gotten to be a more, much, much more analytical type of role that helps people not only to tell what happened, but also to make decisions about what they should do.

JM Rieger: VORPs, WHIPs, and WARs have replaced traditional measures in America's pastime. Not actual war, but wins above replacement, which shows how many wins a player gives a team compared to another player. WAR took center stage in the American League MVP race last year. Detroit Tigers third baseman, Miguel Cabrera, captured the Triple Crown for the first time since 1967, and although Cabrera ultimately won the MVP as well, Los Angeles center fielder and Rookie of the Year, Mike Trout, almost stole the show, holding the advantage in one distinct area, WAR. Noe says the 2012 MVP race speaks to a larger trend in baseball.

Doug Noe: Different looks at what you decide to value then kind of get you into the argument of who is more deserving player for Most Valuable Player. Before some of the more interesting analytical work came along in the last few decades, I think that it would have been a near unanimous decision that Miguel Cabrera, the Triple Crown winner, would be the Most Valuable Player.

JM Rieger: However, had Trout won, it would not have been the first time a Triple Crown winner did take home MVP, as Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig and Ted Williams failed to do so. Miami sports information director, Jim Stephan, says statistics are just one part of the picture.

Jim Stephan: A player still has to make plays. If you are 0 for 10 against left-handed hitting, you know, if you go up and get a hit, then it's all out the window, now you're 1 for 11 and who cares, you just got a hit. So you still have to perform; the stats are an indicator of how you have performed, but it's an indicator.

JM Rieger: And if 2012 is any indication, fans will likely not reach a consensus on how to judge a player's value any time soon.

Bob Long: Our thanks to JM Rieger for a, kind of a thought provoking piece to get us started here today. Joining us for Stats and Stories are regular panelists for our show, Miami University Statistics Department Chair John Bailer and Journalism Director Richard Campbell, and our special guest today is Jim Albert. He co-authored a book called Curveball, which really delves into the stats of baseball. He's also a statistics professor at Bowling Green State University. You know Jim, I grew up in the '50s with a mother who loved baseball, this was back in the day when the Cleveland Indians were a good team, but I learned from her all about batting averages, home runs, and I think back then we had the discussions of whether a guy like Ted Williams should be the MVP, as well as winning the Triple Crown, but today it just seems like there's so many more stats out there that are used. Am I correct about that? It just seems like it's changed dramatically.

Jim Albert: Well I think now there's a lot more different ways of measuring people's contributions, especially in defense and pitching. I think we understand a lot more about that than we used to. And to me, it just adds to our enjoyment of the game; we understand these players better.

Bob Long: It seems to me that there are some fans that just love all kinds of stats, so adding a new level doesn't really bother them. I suppose there are other people though that never get into the stats at all.

Jim Albert: That's true, I think especially when you go to a game and look at a scoreboard now, when someone comes to bat: they give you stats. You want to get an understanding about how good the player is, and I think adding these additional measures gives you a better understanding of what they're contributing to the team.

John Bailer: One of the things that I've seen is that baseball seems to be much richer in terms of the statistical information that's part of it. As well as all the work in baseball that you've done, as editor of the Journal of Quantitative Analysis and Sports, you probably see lots of other applications, but I was curious if you could comment a little bit on why baseball has been so rich in this tradition of use of statistics and summary of performance, and other sports seemed to have somewhat lagged behind.

Jim Albert: Well, I think when the game started, this is back in the 19th century, I think they wanted to make it more credible and by collecting statistics from day one, they started to collect things like runs, and that was collected; batting average is a very old measure. And also, I think baseball has a very nice, discrete structure, so it lends itself well to statistics because you've got a basic confrontation between a batter and a pitcher. A basic result, you have three outs in an inning; you have nine innings. Other sports, like basketball or soccer, are much more continuous in time, so they're much harder to quantify.

Bob Long: That's kind of one of the things I was wondering about too, because it seems to me in baseball there's just more, as you mentioned, that individual, man-on-man, kind of confrontation, where there's so much more team elements to other sports, not that there aren't in baseball, but there seem to be more of that in baseball.

Jim Albert: Yeah, like in basketball, for example, a shot is scored, but of course maybe the person made the shot because of a good pass. Well in baseball, when a person hits a home run, well clearly that contribution was made by the hitter; it wasn't a teammate, so it's a different kind of thing.

John Bailer: Have you seen, over time, an evolution of some of the defensive and pitching summaries, more so? Because early on, it seems the history has been with the offensive summaries, that they were very rich and pretty minimal, maybe errors on defense or runs allowed for a pitcher.

Jim Albert: Yeah. I think, for example, fielding percentage has been the classic measure of a fielding performance, and that basically says of all the balls you played, what proportion did you make successfully? And of course, it ignores all the balls that you didn't play, all the balls that went beyond your range. So actually people understand that fielding is a lot more about range than actually catching a ball or making a play that is hit to you, so now we're actually able to measure where fielders move. We can actually quantify the movement and we have a much better understanding about range.

Bob Long: That was one thing I know if you went back and looked and had a third baseman who had five errors in a season and said, "Wow, he was a great third baseman," but if there were a lot of balls that he didn't get to, he wasn't such a good third baseman after all.

Jim Albert: Yeah. You can imagine if you had a third baseman that just stands still and doesn't move, well he'll do great at balls that are hit to him, but not be very useful to the team.

Bob Long: You're listening to our program, called Stats and Stories; our discussion today focusing on baseball and the importance of statistics. Our regular panelists are Miami University Statistics Department Chair John Bailer, Journalism Director Richard Campbell, and again our special guest Jim Albert, who co-authored a book called Curveball and he's also a statistics professor at Bowling Green State University. Well, you know, we thought it would be fun to go out and we sent our Stats and Stories reporter Colleen Rasa out to talk to people, many of whom really didn't know a whole lot about baseball; maybe they watch or listen to it a little, but they're not die-hard type fans. We wanted to just know what they knew about stats and their relevance to the game of baseball.

Woman on the street #1: To keep up with the players and track the teams, I guess.

Man on the street #1: Batting average. There you go, batting average.

Woman on the street #2: I only know one thing, and that's RBI, so I guess all of the rest of it is confusing.

Man on the street #2: RBIs, uhh, it's basically when someone's on base and another batter hits that baseball and the other person scores; it's considered an RBI for the person that hit the ball, even if they got out.

Woman on the street #3: What is an ERA even? Who knows?

Man on the street #3: I think it's just a good way to track how the players are doing on an individual basis.

Woman on the street #4: When you bunt the ball, it's not really a stat, but when you bunt the ball sometimes it can count, and sometimes it doesn't, and it's confusing to me.

Man on the street #4: ERA: Errors per game, for a pitcher. Depending on how many errors, how many hits they get on the field, if someone gets on base, it's an error.

Woman on the street #5: I don't know. I don't know any of the stats; I'm a hockey fan and I watch hockey.

Man on the street #5: They do a lot of new stats these days, with like the submetrics, that I don't really get into or pay attention to.

Woman on the street #6: I know what like .500 is, like if they bat .500 it just means that they strike out as much as they get a hit.

Bob Long: Well there's a few things that are just slightly off base. Gosh, a stats guy like John Bailer, that's got to drive you nuts, "submetrics." I think they meant sabermetrics.

John Bailer: Yeah, yeah. Close, but no cigar. And I guess it's appropriate that the show has somebody starting in an off-base position here. So Jim, could you talk a little bit about the sabermetrics? Where did that come from? And what exactly does the "saber" mean in this context?

Jim Albert: Well, there is a group of people in the 1970s that were especially passionate about baseball, and passionate about the history of baseball, and so they started an organization called SABR, the Society of American Baseball Research. So about that same time, Bill James was talking about quantitative analysis so it seemed natural to use the phrase "sabermetrics" to correspond to the quantitative analysis of baseball.

Bob Long: I'm just kind of curious, when did you get started? When did you get interested in all of this?

Jim Albert: Well when I was growing up, I loved baseball; I was a baseball fan and I liked math and I liked to play probability games in my basement. I played games like All-Star Baseball and Strat-O-Matic and would play a whole season and keep stats. It was fun, I really enjoyed learning about the players and knowing about their statistics.

John Bailer: Yeah, it's neat to see. Is there something equivalent to sabermetrics in other sports? I don't know of anything that has that kind of "metrics" before it in other sports.

Jim Albert: Well, I think what's happening in other sports is they're basically following the lead in baseball. For example, situational stats, which are very popular in baseball, now we're talking about situational stats in football and basketball. So it's more than how you do; it's how you do in special situations.

John Bailer: So can you give an example of situational statistics and summaries that you might see in a different sport?

Jim Albert: For example, there's this home versus away affect; how you perform at home games versus away. Generally, the home team is more likely to win and the advantage of the home team depends on the sport. In baseball, it's relatively small; in basketball, it's larger. We talk about how people perform in the clutch. You know, when it's an important situation in the game, how do you do? And people like to think that people have what is called "clutch ability," the ability to do a special performance when it's an important situation. Reggie Jackson, he's called Mr. October because he performed well in October. Dave Winfield was called Mr. May because he didn't do as well during the World Series. So to me, I don't believe in "clutch ability," I believe in "clutch performance," but I think people like to talk about that because that indicates something about the value of the player.

Bob Long: Richard Campbell?

Richard Campbell: Jim, how much does this rise in keeping track of numbers and statistics on players, how much is it affecting the old coaches and managers that used to make decisions just based on their gut and go with their heart? And do we actually have statistics on how often they're wrong, and how often they're right in making those kinds of decisions?

Jim Albert: I'm sure they do, and what's interesting about baseball is that some teams have really embraced the sabermetrics movement, and I think it may be that some teams do use quantitative analysis when to decisions about managing, and other teams probably don't. They might use metrics more for scouting players, especially when they draft players, but I think a lot of the managing going on in baseball is the same as it was thirty years ago.

John Bailer: As a follow-up to the use of some of these statistics and summaries, there's been controversies associated with things like steroid use and abuse by some of the players. Can you talk about how some of these summaries have been used to perhaps support or identify something in a performance that you wouldn't expect?

Jim Albert: Well if you look at Barry Bonds, and look at his performance through his career, it is very interesting because he hit his peak and then started to die down and all of the sudden, his performance enhanced dramatically close to forty years old. I'm not saying it was steroids, but there was something that caused that change, and you can see the effect statistically.

Richard Campbell: As the story guy here, the guy from the humanities who also is a big baseball fan, I argue when I talk about narrative that people are drawn to sports because they are organized like stories, they have a beginning, middle, and end; they having rising and falling action; they have good guys and bad guys; and most of all, conflict and dramatic tension. So my question here is where does stats fit into this picture? How do they enhance the sort of narrative of the game? Because we just heard from all these students, and the general public, who appreciate baseball at a level that is sort of not statistical, and I'm also fascinated, as a humanities guy who is an English major, I kept track; I love the numbers; I love reading statistics. There's certainly something that enhanced the game for me, following numbers in sports.

Jim Albert: I think a box score of a baseball game is the story of the game. I also think that some stories are defined by statistics. For example, you think of DiMaggio, and you've got to think about the 56 game hitting streak; that was his story. Think of Cal Ripken and his however many consecutive games he played. You think of Ted Williams hitting .406. That's a great story: last day of the season and the manager was suggesting he be benched because he might fall below .400 and Ted Williams said no. He played a double-header and actually raised his batting average on the last day; those are great stories.

Richard Campbell: The box score story is interesting. I remember; I still have them. In 1975, I clipped every box from the Cincinnati Reds year because I thought, "This is a good team and they're gonna go." And I saved every one, and I still have them. And it does, you can look at them in order and read them and have a pretty good sense of what the story was.

Jim Albert: If you go to baseballreference.com, which is a wonderful website for baseball stats, you literally can revisit all these legendary box scores.

Bob Long: I think that's kind of interesting, though, because I remember reading a book that Sparky Anderson wrote after the Tigers went to the World Series, when he had switched from the Reds to the Tigers. But it seems to me that he had a lot of box scores in there, but it seems to me that true baseball fans really fall in love with that element of the game.

Jim Albert: Yeah. I remember, I grew up and I remember so well Jim Bunning. I was a Phillies fan and Jim Bunning pitched a perfect game on Father's Day, and I still remember that box score. I remember where I was when I watched the game on TV, but I think it's a beautiful box score because you see all those zeros. Bunning faced 27 hitters. It was perfect.

Bob Long: You don't find a box score that looks like that too often.

John Bailer: So which of these records do you find as kind of the most dramatic story? And sort of related to that, which do you think is going to be the hardest to break?

Jim Albert: I think the 56 game hitting streak is probably one of the hardest ones to break. I think nowadays it's difficult to even have the opportunity to hit during a game, so now I think there would be a lot of pressure. I think once a player gets into a streak, there's a lot of discussion about it and there's a lot of pressure to continue hitting. That's a remarkable record.

Bob Long: We'll take a quick break, but you're listening to Stats and Stories, and of course we are focusing, for this week's show, on the role of statistics in baseball. I'm Bob Long; our regular panelists that you've been hearing, Miami University Journalism Director Richard Campbell, Statistics Department Chair John Bailer, and our special guest today, Bowling Green State statistics professor Jim Albert, who is also co-author of the book Curveball, which again delves into the use of stats in baseball. Again, our own Colleen Rasa went out and was curious if fans really understand what the baseball statistics are being used for today.

Man on the street #6: It's money based, too. Whichever team has better players and better stats, they're going to make more money and have more for their program.

Man on the street #7: They're used to record pitching, fielding, batting, percentages of games that are played, percentages of people that show up that don't want to pay $400 for a seat.

Woman on the street #7: They are used to follow which player is doing the best, or which team is doing the best, the way I see it.

Man on the street #8: Typically, whoever has the better stats will bring the team along to the World Series.

Man on the street #9: It tells you who the key players are on the lineup; who's going to be first, who's going to be second, who's going to be third. It gets you an idea of how the team's going to do through the year.

Woman on the street #8: Um no, because I'm a baseball fan in the fact that I like to go to the Reds games, we sit in the five dollars, bleachers, we drink beer, and so if they get a hit, it's fun, but if they don't, we boo and hiss. Stats make no sense to me.

Bob Long: I can't watch a baseball game like that. That's just not part of my DNA. But I do think it raising an interesting issue, because we kind of heard the word "money" mentioned in there, and I think that's another thing that dramatically changed what's going on because, I, as a fan, may use baseball stats to look at one thing, but managers and owners look at it in a much different way. And of course, agents of players also use it much differently today.

Jim Albert: Yeah, I think what's happening now in baseball is that players are moving a lot more between teams because it's all about contracts. I follow the Phillies, and everybody is talking about Chase Utley because his contract is up at the end of the year, so people are wondering if he will be worth resigning after the season. And unfortunately, that's a big part of it, and great players will move. Albert Pujols; hard that he would leave the Cardinals after so many years, and it all came down to money.

John Bailer: Do the players start to use some of these new statistics to argue for value? I mean it seems like there's sort of two levels to this: one is the teams that are deciding who to try to acquire, but also, are the players able to leverage their performance on some of these metrics?

Jim Albert: I'm sure they are very aware of these performances, and they use it as leverage for the contract. It's an important part of their game now.

Bob Long: Richard?

Richard Campbell: In your book Curveball, you make a distinction between sports statisticians and professional statisticians, which is kind of interesting. Could you talk about that a little bit?

Jim Albert: Well, I think there's a confusion about the word statistics, because we think of the people who are just tabulating the data, and they're called statisticians. But to me, a statistician is somebody who actually interprets the data and tries to draw conclusions, or uses for prediction, that's more what we're talking about. There will always be that confusion because we use the word in two ways.

Richard Campbell: You talk about the professional statisticians, like you and John, use models as a distinction between information. Give us an example of that. You talked about one example, which is the old games some of us used to play.

Jim Albert: Well for example, baseball competition, I mean, basically teams have different abilities, but the point is they play each other, and there's a role of chance involved in who actually wins the game. So you can use a model to describe the role of chance. You can actually quantify how much, you can actually quantify "what's the probability that the best team, the team with the most talent, wins the World Series?" And that's done by using a statistical model.

John Bailer: One feature that I thought was interesting in the comments was the idea that the team with the best stats will win. Do you have classic examples of some of the traditional statistics where a team that looked really great on some of the traditional summaries just didn't perform well, but the new metrics might highlight that and explain it?

Jim Albert: Well for example, batting average is not really a good measure because it ignores things like getting on base with a walk, and really the key issue, there's two issues: one is that you want to get on base, and on base percentage measures that, and you also want to advance runners that are already on base, and like a slugging percentage measures that. So unless you talk about both of those things, you really are missing out on what's important in baseball scoring.

Bob Long: I'm kind of curious, though, there are some stats that I wonder how valuable are they. You'll hear a play-by-play announcer, for example, say "Well, so and so only bats .125 when the bases are loaded," like they are at that particular moment. Does that really mean as much, because maybe that guy, if he's batting .125, had only been to the plate eight times with the bases loaded, which doesn't seem like much of a measurement that you can use.

Jim Albert: What they never tell you is the sample size. And sometimes, the sample size is so small, so really, with small samples, you get a lot of variability. This also happens with pitcher-batter match ups. Sometimes you'll have a certain batter who does really well against a certain pitcher, but that's over many years, so really it's not a very meaningful statistic, but unfortunately, managers often make decisions based on that kind of data.

Richard Campbell: My job running the journalism program here is to help our students think about incorporating numbers and data into stories and how do you tell stories that use numbers and data? In general, how well do you think sports reporters do using stats and numbers, and what do you think they do well, and what aren't they doing so well?

Jim Albert: Well, I think it's harder for them to use more modern statistics, because they're not really able to understand what they mean. For example, if I tell you that an OPS value was 1.200, you probably wouldn't understand that, but a batting average above .400, there's certain statistics in baseball that have a very strong understanding. A .400 batter is a great hitter, winning 300 games in a career is a great accomplishment, 20 wins in a season for a pitcher is considered good. So I think these always will be easy to talk about because everyone understands them.

Bob Long: I know one that I've got to throw in today, and I was just reading up on this today. George Brett, who was one of the last guys to come close to hitting .400, I think he finished around .390, but at one point he wasn't doing too well and his teammates were making fun of him that he was approaching the Mendoza line, referring to Mario Mendoza, a short-stop who was a light hitter who kind of lowered the benchmark. He couldn't even hit .200, and the .200 level has kind of become a benchmark. How much does that happen that you see certain things that really aren't necessarily statistically backed all of the sudden become a very popular thing in the media that everybody refers to like that?

Jim Albert: For example, currently, we think that 100 pitches in a game for a pitcher is one of those things that you don't want to break. Once a pitcher throws 100 pitches, he's out, and I really think that in five years, we're going to change that; it won't be 100 pitches anymore. I think we're still learning about pitcher fatigue, and we're so worried about injuries. But I don't really think that there's any evidence to say that 100 is the right number, but once those numbers are used, they become the number that everyone thinks to use.

John Bailer: Do you think some of these new metrics that are coming about are starting, we've talked about them influencing player selection and team management, we talked a little bit about them modifying what's happening during the management of the game, game management, not just team management, where do you see the greatest opportunity for increasing the impact of these ideas in the game?

Jim Albert: Well, I think, for example, on the decisions like on how to advance runners, advancing to second base, those kind of things, I think people have to use stats to understand the value of those things. I think running in baseball is not as well understood as we'd like to think. But nowadays, there are ways of measuring the contribution of running. So it's going to be a while before those things are accepted. We still focus on things like batting; that's easier to measure.

Bob Long: Are there other areas that you think eventually, you mentioned the running aspect, other things where you think we're going to see more of that in the future in baseball? Because it seems like a lot of people think that we're saturated out right now, but do you see other things that are on the horizon?

Jim Albert: Well currently, every single pitch that's thrown in baseball is photographed, so we have measurements on the trajectory, the movement of pitches, the type of pitches. Everyone is talking now about how Roy Halladay's pitch speed. That's been important. I think what's going to happen now is we're also starting to measure things like fielder location, locations of hits, we can actually quantify, we can talk and say this person hit so many line drives. So we're starting to learn even more about baseball.

John Bailer: Question, what sport do you think is going to be the next one that's going to be majorly impacted by the analytics of sports?

Jim Albert: Well, I think that the sport in the world that's the most popular is soccer, and I think that's the area that I think people are trying more and more to use baseball types of measures, but it's much harder to quantify. I think the fact that they're measuring the spatial locations of players is going to be a positive thing and eventually will get better measures.

Bob Long: Jim Albert, thanks so much for sharing your insights on baseball with us on this edition of Stats and Stories. We'd like to invite you to check out our website. It's statsandstories.net, and be sure to listen to future editions of Stats and Stories, where we'll discuss the statistics behind the stories, and the stories behind the statistics.